Contents

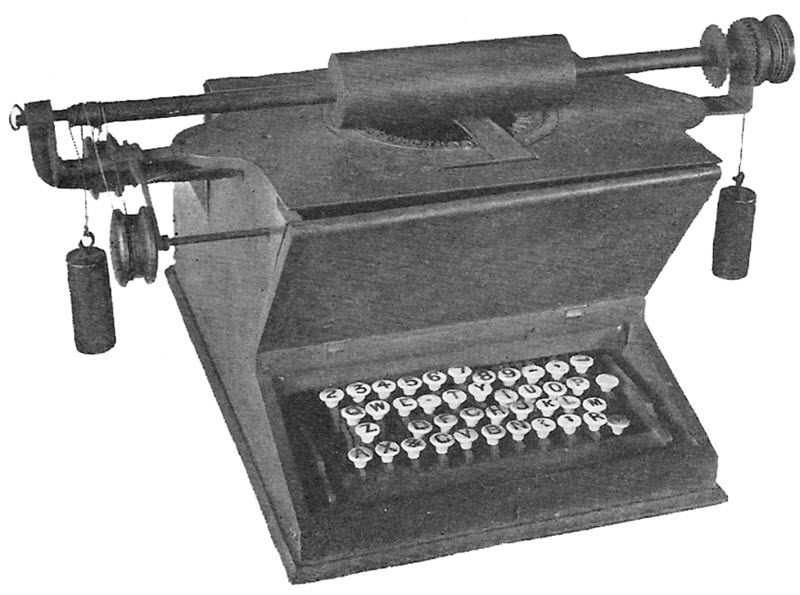

The Sholes and Glidden typewriter was launched in 1874 and eventually became a huge commercial success. The first commercially available version of this machine is also known as the Remington No. 1, and it was to be followed by Remington No. 2 in 1878.

For the first ten series, the writer could not see the text during typing, as the paper was hidden inside the machine. It would take until the launch of the Remington No. 10 in 1906 before a so-called “visible” Remington typewriter became available.

Background

The main designers of this typewriter was Christopher Latham Sholes, Samuel W. Soule and Carlos S. Glidden – all three based in the United States. Developmental work commenced in 1867, but Soule left the project shortly thereafter and was replaced by James Densmore.

E. Remington and Sons

The developers made several attempts to manufacture their device, but had little success. In 1873, the arms manufacturer E. Remington and Sons contracted to manufacture 1,000 machines, with the option to produce an additional 24,000 if they wanted to.

After some additional developmental work, the Remington company launched the Sholes and Glidden typewriter on 1 July, 1874.

A slow start

Initially, consumer interest in the Remington No. 1 was weak, and by December 1874 only 400 typewriters had been purchased. This was due to a combination of factors, including high price and poor reliability. Even though typewriters had existed even before the Remington No. 1, they were not in widespread use in the United States and few people knew how to use one. The Remington No. 1 cost circa 125 USD and not many companies and professionals produced enough written texts in a year to justify the cost. Also, the machine could only write upper-case letters, which many people found ugly and impolite.

It wasn´t until several improvements regarding both design and manufacturing process had been implemented that the Remington typewriter became a commercial success. From Remington No. 2 and onward, the machine could write both upper-case and lower-case letters.

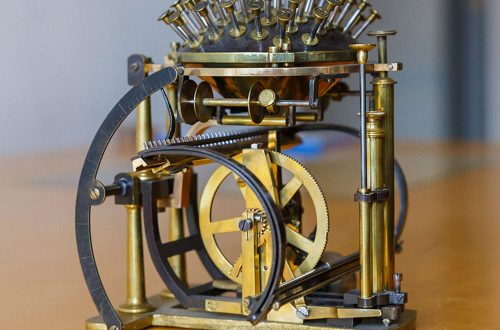

Design

Several of the design elements of the Sholes and Gidden typewriter are still considered industry standard today, and can be found even on modern-day computer keyboards.

One example is the QWERTY keyboard, where the first five alphabetic characters on the top-row of letters are Q-W-E-R-T-Y.

While the older Hansen Writing Ball invented in Denmark was design to promote very speedy writing, the QWERTY keyboard did not have this as its primary focus.

The first model created by Sholes had actually had just two rows of characters, and they were arranged in alphabetic order on a piano-like keyboard. Schwalbach replaced the piano-like keys with button-like keys and spread them out over four rows. The alphabetic arrangement proved problematic because pressing nearby buttons in close succession caused their typebars to collide and get stuck to each other. Therefore, the characters were moved, and the characters used most frequently in English were placed far away from each other.

Women typewriters

In their marketing of the typewriter, Remington promoted the idea of women being ideal typists and that typing was an appropriate profession for a woman.

Even before the Remington company got involved, Shole´s own daughter was employed to demonstrate the machine to prospective customers, and she also appeared in promotional images.

The Remington company hired more women to demonstrate the machine at trade shows and in hotel lobbies. To overcome the idea that the typewriter was overly complicated, early depictions of female users suggested that it was actually “easy enough for a woman” to use.

The Remington company manufactured both typewriters and sewing machines, and using elements from the sewing machine section saved time and money. Therefore, early Remington typewriters were displayed with sewing machine stands and floral ornamentation.

By 1881, the association between typewriters and women had become so strong in the United States that the Young Women´s Christian Association (YWCA) established a typing school where women were trained by the manufacturer Soon, their typing services could be provided to customers along with the machine.

Hiring women instead of men cost less, which in turn made the use of typewriters more financially feasible for businesses Even though women were paid less than male clerks, a job as a typewriter would still pay several time more than the jobs available to women in factories. In 1874, less than 4% of formally employed clerical workers in the United States were women. By the turn of the century, that number had rose to 75%.